Bulls on a copper high: Why copper prices are rising

Originally published at 01.03.2021 by Stefan Eppenberger Reading time: 7 minute(s)

In the first few weeks of February 2021, one market grabbed the spotlight that many investors had almost forgotten: the commodity exchanges. Copper, in particular, became the talk of the town, rising to a multi-year high. Read more on this theme and find out why it is blazing a new investment trail in 2023.

WHY THIS TOPIC IS RELEVANT IN 2023

Underinvestment in commodities highlighted against the background of climate change and technological progress

Commodity exchanges have re-emerged into the limelight because raw materials such as copper, lithium and nickel are critical elements in the technologies of tomorrow.

- Rapid technological progress driven by the growing world population and wider distribution of electronic equipment mean that requirements for these and other raw materials are set to grow significantly. Our mobile phones, computers, the growing number of electric vehicles on our roads and solar panels on our roofs could not function without the veritable periodic table of minerals and metals they contain.

- In addition, to achieve the goals of the Paris climate agreement, a transition from fossil fuels to renewable energies is essential and that would likely mean increasing production of batteries, electric engines, wind farms and solar panels.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that energy technologies’ share in the overall demand for copper and rare earths will grow to over 40 percent in the next two years. In the case of nickel, growth is expected to be 60–70 percent and for lithium almost 90 percent.

As a result, companies which extract and process these materials and those operating in the surrounding infrastructure are set to benefit, offering investors attractive investment opportunities.

Expert interview: reasons underpinning a new bull market in commodities

For a good ten years, investors came to see the commodities market as a bear market. Based on this perspective, many of them may not even be able to put what we are currently experiencing into any meaningful context.

Stefan, are we moving now towards a bull market?

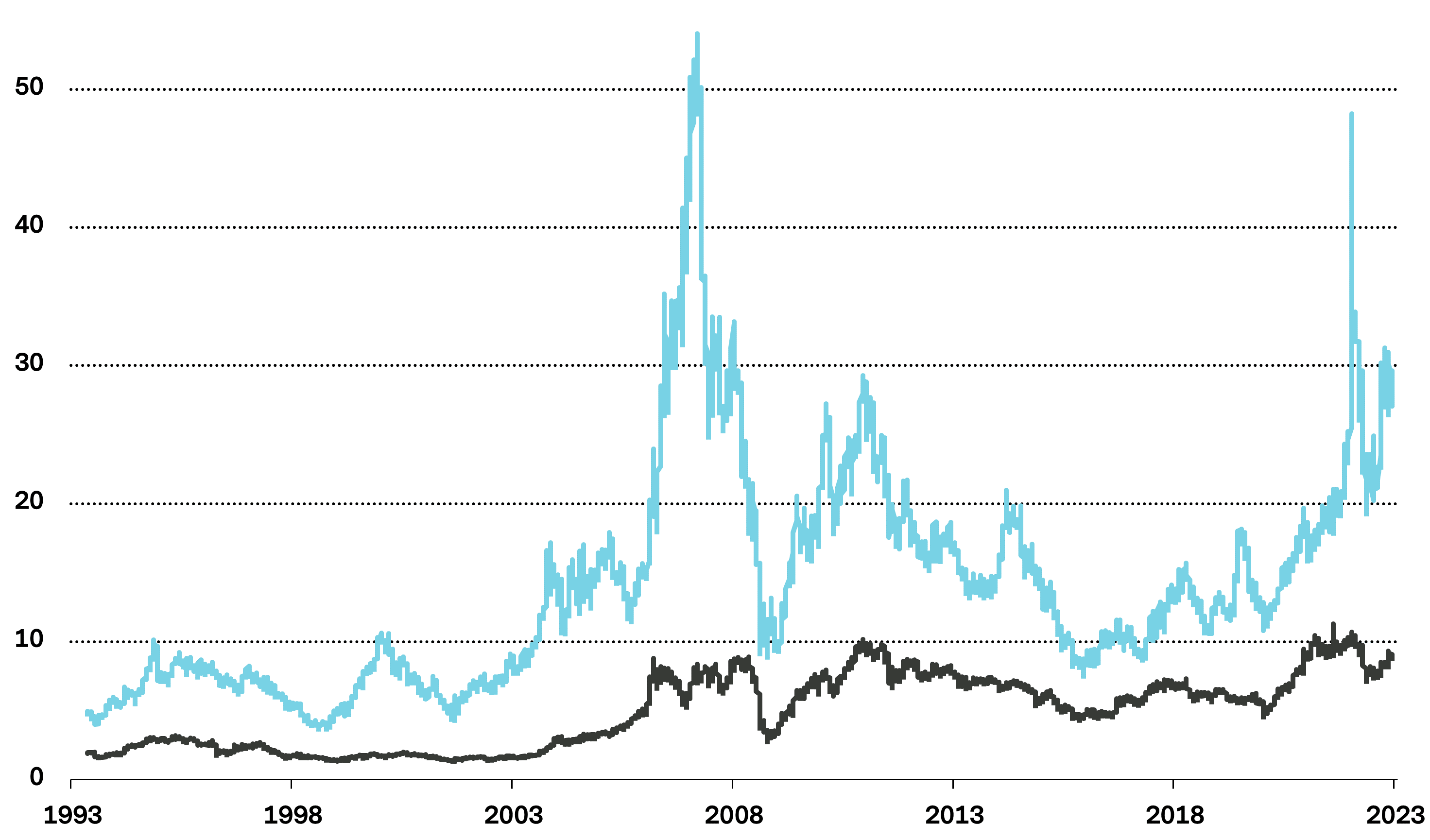

Let me first back up a little and explain how bear and bull markets in the commodities sector come about in the first place. Let’s take the last major commodities cycle as an example, which stretches from the year 2000 to today. A bull market usually starts with a positive demand shock. In the 2000s, this shock was provided by the enormous demand for raw materials from China. Typically, what happens is that in this situation, the supply of commodities can’t keep up with the rapid growth in demand, because mining operations that could increase the supply need several years to plan and execute, and during this preparatory period, the inability of suppliers to meet demand drives prices higher on the commodities exchanges. This bull market lasts until the strong demand weakens. Often this occurs in conjunction with an oversupply of the commodity, created thanks to all the newly built extraction and production facilities finally coming onstream. This constellation – now a glut – causes the price of the commodity to fall, resulting in a bear market. Yet the producers of this commodity still have to monetize their investments, and if necessary, at these lower prices. This is exactly what we’ve seen happening over the past ten years.

What are the reasons that interest in commodities has been rekindled these days? Are we simply dealing with hype – or do you see structural drivers at work here?

Whenever you see prices rising like this, it’s natural that investors get interested! (Laughs.) For the current situation, there are different interpretations about why commodity investments are becoming more attractive. According to some of them, a reversal in the inflation trend is expected, driven by the enormous monetary and fiscal support measures put in place during the Coronavirus crisis. Commodities are generally considered to be a good protection against inflation, so investors would find them attractive right now.

“Commodities are generally considered to be a good protection against inflation.”

However, we think it’s still too early for such an inflation scenario, precisely because after the recent crisis, the rate of capacity utilization at many companies is still too low. (More on the topic of “inflation” in this blog article.)

In our opinion, the commodity price increases since summer 2020 can primarily by explained by fundamental factors. On the one hand, sentiment in the manufacturing sector improved from month to month after the first Covid-19 lockdown. Especially in China, which is known to have mastered the crisis better, commodity demand has risen sharply. At the same time, mining activities to extract these raw materials were severely restricted during the crisis – in part voluntarily, in part forcibly. We also observe that inventories are currently falling sharply, or have already reached multi-year lows.

In addition, there are hopes in the current price rally that a new, positive demand shock could occur. The strong trend towards emission-free forms of energy could introduce some momentum into the world of commodities. In addition, thanks to the low price environment that has prevailed in the past few years, new investments in mining projects have been cut back sharply over the last half decade. So there are definitely good reasons underpinning a new bull market in commodities.

Since mid-February, copper in particular has stood out, with prices hitting highs. Why does copper of all things have this “golden” sheen?

Due to its chemical properties, copper is and will remain irreplaceable in the electrification of the global economy. The enormous regulatory efforts in recent months to combat climate change are likely to result in a paradigm shift. For example, an electric vehicle (EV) requires four times as much copper than in a comparable vehicle with an internal combustion engine. The demand for copper in the manufacture of new solar power equipment, wind turbines and energy storage systems will be even higher. In the past few months, copper has certainly also benefited from strong demand from China, at a time when Covid-19-related supply bottlenecks from South America – the region with the largest copper deposits – were also putting pressure on prices. But precisely because many copper warehouses are already half empty, the metal has the potential to rise in price further, given the increasing demand attributable to renewable energy production. The situation looks similar with other industrial metals, too.

Could you elaborate on the example of e-mobility: What should investors have on their radar if they assume that a big change is coming here?

The big winners of the EV boom are lithium, cobalt and above all nickel. The demand for lithium is expected to triple by 2030, while that for cobalt and nickel will at least double. From 2030 on, demand is likely to increase again sharply. This depends heavily on how quickly electric cars can gain market share. According to forecasts by BloombergNEF, the share of global auto sales attributable to EV’s will grow from less than 3% today to more than 20% in 2030. By 2037 at the latest, the number of electric vehicles sold should be higher than those of cars with internal combustion engines. (Read more about the boom in EVs.)

“By 2037 at the latest, the number of electric vehicles sold should be higher than those of conventional cars.”

So the question arises whether global supply will be able to keep up with this rapidly increasing demand. In principle, sufficient reserves do exist. Even if you disregard additional supply created through recycling or by finding new sources, by 2050 we will only have exhausted less than 50% of total global reserves. What is less clear, however, is how long it would take to extract and process these commodities. Several factors could affect this. First, since prices are relatively low, many mining projects currently remain on hold. Second, China and other emerging economies will continue to need large amounts of these metals, particularly nickel, to build their infrastructure. Third – and this is especially true for cobalt – some of the places where these mining activities are undertaken are politically unstable.

Finally, let's take a look at the other side of the equation. If e-mobility increases, this also has consequences for the oil, gas and coal industries. How are they currently reacting?

The move away from internal combustion engines is likely to have negative implications for oil demand, as the global transport industry is currently the main buyer of black gold, accounting for over 50%. Road traffic makes up the largest share of this amount, around 75%. Of course, the global car fleet will still be dependent on gasoline for some time to come. And thanks to the structural trend towards more mobility in the emerging countries, the overall vehicle fleet will continue to grow. Nevertheless, it is expected that demand for oil – generated by road traffic – will peak in 2030. In addition to the switch to EVs, efficiency gains within the internal combustion engine itself will also contribute to reversing this trend, as will the trend towards ride sharing. So even though the total demand for oil will continue to rise even further due to the needs of the petrochemical industry, the EV boom is likely to be the deciding factor that brings about the end of the Age of Oil.

“The EV boom is likely to be the deciding factor that brings about the end of the Age of Oil.”

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that oil prices will plummet into the abyss. Due to the recent low price levels of oil, investment in new sources has decreased significantly. The negative demand outlook I mentioned before is likely to result in at least private-sector oil companies being very reluctant to undertake the costly search for new sources. But it cannot be ruled out that at some point before the end of the Age of Oil, supply bottlenecks will result in skyrocketing prices once again.

Are you looking for access to our investment experts?We look forward to answering your questions.

|

|