Most investors welcome dividends. Even the founder, CEO, and Chairman of a Swiss biotech company who for years advocated reinvesting every penny made back into his company, once told us that he was thrilled when he received the first dividend payment from his company—it gave him a feeling of satisfaction. For individual investors, receiving dividends is often a welcome cash inflow. In the case of institutional investors, such as insurance companies or pension funds, it helps them fund ongoing expenses.

Generally speaking, investors and companies attach considerable importance to dividends. In the US, “Dividend Aristocrats” constitute a stock market index of companies in the S&P 500 that have paid and increased their base dividend in each of the past 25 consecutive years. On the downside, however, an unexpected cut in the dividend of a “dividend” stock (high, reliable dividend payment) often leads to a very negative share price reaction as it is considered by investors to be a major negative signal regarding the company’s long-term prospects.

Benefits of dividends

One of the long-term benefits associated with stocks that pay high dividends are potentially stronger returns and lower volatility—under certain circumstances, dividends may help cushion losses during bear markets. If we take the last three bear markets, when the S&P 500 declined over 30 percent, the “S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats” outperformed the S&P 500 Index on two occasions. First, during the bursting of the tech bubble (September 2000 to October 2002) and then again during the Global Financial Crisis (October 2007 to March 2009). In both cases, the outperformance was significant or even very significant. More recently, during the COVID-19 sell-off, the “Dividend Aristocrats” marginally underperformed.

How to explain the different performance of dividend stocks?

The stellar outperformance during the bursting of the tech bubble should be not surprising. Technology companies are mostly growth companies: They reinvest their capital rather than distributing it to shareholders. Thus, the absence of technology stocks in the “Dividend Aristocrats” was the driver of the outperformance.

In turn, given that technology and growth stocks in general benefitted, at least to a certain degree, from some of the effects related to the COVID-19 pandemic, “Dividend Aristocrats” marginally underperformed. In light of the above, the question must be asked:

“Is the outperformance of the ‘S&P Dividend Aristocrats’ a function of the dividend, or rather the generally more defensive business model of its constituents, compared to a much higher share of growth companies in the S&P 500?”

Not all dividends are the same

Dividends cannot simply be taken at face value, as not all dividends are the same. Their future development, such as growth trajectory, stability, or predictability, depends on company-specific factors.

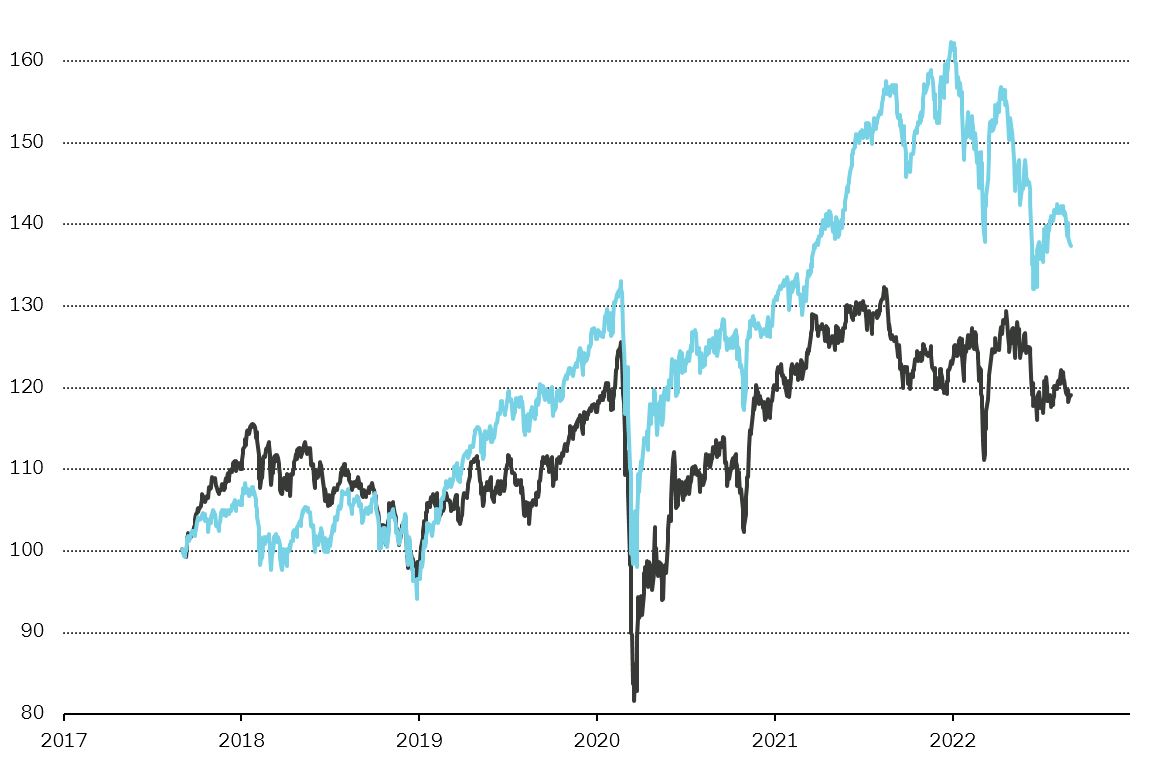

Investing in companies with the highest dividend yield risks falling short of a sound, long-term investment strategy. For illustrative purposes, we create an equal weighted portfolio over the last five years which includes the ten Swiss SPI stocks with the highest dividend yield at the time (we excluded micro-cap companies). Over this time horizon, the total shareholder return* of the portfolio underperformed the benchmark (SPI) even under the assumption of zero taxes on dividends and no transaction costs.

* Total return here: Capital appreciation plus dividends

Consequently, investors should assess each company’s dividend prospects and diversify their investments. A high dividend yield can be the result of a company’s strong cash generation, a sign of distress, or a lack of growth opportunities.